Love Me Tender

These days, corporate debt management, mainly through buybacks or exchange offers, are quite common. For bond repurchases, the approach can vary depending on each company’s objectives.

In this Opinion Piece published in La Lettre du Trésorier N°421 June edition, Stéphanie Besse, Head of Corporate DCM, and Mark Soriano, Liability Management expert, examine the market forces and internal corporate drivers that create room for debt optimization.

They also explain the solutions available to issuers, focusing mostly on public tender offers on bonds, being the most commonly used tool in the market.

Rising interest rates, a brake?

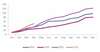

In the euro bond market, at least fifty-two tender offers have already been carried out so far in 2024, which represents a marked increase compared to previous years (see graph). On the face of it, this result appears somewhat contradictory against a backdrop of rising interest rates. Why would a borrower be inclined to retire debt bearing coupons that had been set in an ultra-low-rate environment?

Number of EUR Tender Offer in EMEA

Source: Natixis CIB

Multiple motivations and objectives

The answer lies with how borrowers strategically wish to address the shift in rates and market environment. Some issuers simply wish to reduce debt levels, perhaps with the added benefit of doing so at discounted prices. Others think of debt buybacks as an alternative investment for cash, or a way to reduce negative carry in an early refinancing aimed at taking advantage of robust market conditions for issuance.

Tender offers have also been used for more strategic objectives ranging from a rebalancing of a company’s debt currency mix to corporate re-organizations including issuer substitutions and relocation of debt in the capital structure.

In short, there is no generic answer. And the need to conduct a debt repurchase would depend on a company’s strategy on leverage and cash management.

What are the borrower’s options?

A borrower can repurchase its own bonds privately or publicly.

Private or so-called ‘open market’ transactions are discreet and typically gradual purchases of bonds from the secondary market. The borrower engages a bank to repurchase its bonds through the bank’s market making activity. The approach is opportunistic and is typical for issuers who have a more modest quantum of bonds in mind to repurchase or cash to deploy.

Alternatively, the borrower can also launch a public offer to purchase one or several bond tranches. Such transactions are oftentimes combined with the issue of new bonds, with the issuer engaging the same set of banks in both legs of the transaction to facilitate reinvestment by investors. Public tender offers are used by borrowers who want to repurchase a meaningful amount of bonds in a reasonably short period of time.

Instead of delivering cash for purchasing bonds, issuers can also pay investors in the form of new bonds (an ‘exchange offer’) although the approach is more appropriate for select circumstances where there is a need to take advantage of a captive investor base.

How a public transaction works

A market announcement is made indicating the company’s intention to buyback certain of its bonds along with the terms and conditions of such an offer. The bank lead managers advise the issuer on the best strategy and offer structure to adopt, as well as the appropriate price to offer investors.

It is highly unlikely to fully buy back the notional outstanding of a bond via a public offer as investors decisions are not always driven by price (for example, certain investors may be restricted from selling their position as a matter of fund policy). It is due to these idiosyncratic behaviours that the interest to sell by investors becomes inelastic at a certain price point.

The offer usually takes place over five to six working days. This is the amount of time that is practically required for investors to be made aware of the transaction and to have the time to participate via the clearing systems.

Price setting

The value offered to repurchase notes is typically set to ensure that it outbids market makers so as to capture a substantial volume of notes.

An offer can feature a fixed price pre-determined by the issuer at the launch of the offer. Such an approach is usual for bonds that either have a short duration (less than one year) or for high beta instruments that trade on a price or yield basis.

Alternatively, repurchase terms can be expressed in yield terms, specifically as a fixed spread over a certain benchmark (e.g., mid-swaps in the Euro market). The final price is therefore only known after the offer expires when the offer is priced. This approach helps ensures that the value of the offer (expressed as a credit spread versus the risk-free rate) is maintained despite any volatility in rates. This option is thus more common for bonds with longer remaining maturities and/or instruments with low beta.

Rather than fixing terms at the outset, issuers also have ability to undertake some form of picing discovery via a Dutch Auction. In its ‘Modified’ form, the issuer sets a minimum price (or maximum spread) and invites investors to bid at or higher than such value. Upon expiry of the offer, the issuer determines a clearing value which will enable it to purchase the desired notional amount of bonds. Investors who bid below the clearing price are paid the same price. The ‘Unmodified’ form is less common in France and employs a similar system except that investors are paid the price they indicated in their bid.

The capped offer

While the offer is typically open to all holders of the bond, the issuer may be willing to purchase only some of the bonds. In other words the offer could be limited to a fixed notional or cash spend amount. The issuer could target one or multiple issues or groups of bonds.

Where a non-US offer is made on multiple bonds, the issuer would have the ability to buy back more of some bonds than others if the offer is oversubscribed, or to follow a ‘waterfall’ order of acceptance. Where tenders exceed the cap, acceptance can be made on a pro-rata basis. Alternatively, the issuer also has some flexibility to increase the cap and accept all tenders in full.

To fully cancel an issue, the so-called make whole clause exists

The majority of bond issues these days have a ‘make whole’ clause, which allows an issuer to conduct an early redemption of the notes, whether partially or in full, at contractually pre-agreed terms. The mechanism seeks to adequately repay investors for all the future coupon and principal of the notes and can be triggered by simply notifying holders.

The ‘make-whole’ price is typically the higher of par and a price that reflects a bond yield equal to a certain spread plus a risk-free benchmark rate. Such spread is generally set at 15% of a bond’s re-offer spread. (if a company initially borrows over 10 years at the 10-year French government bond rate (10-year OAT) + 100 bp, then it could buyback the issue at the French 10-year government bond rate +15 bp).

In a low-rate environment, this option more often represents a significant cost for the issuer. The notice period can be a month with the issuer having the ability to pre-hedge the changes in the benchmark rate.

Within a refinancing framework

As tender offers are most commonly executed together with a new bond issue, the issuer now commonly prioritise investors who sell their bonds in new issue allocations, which facilitate investor re-investment especially for smaller funds which may otherwise be squeezed out during the new issue process.

This process can be done informally (via investor dialogue with banks), or in a more formal manner, using priority allocation codes that is passed between investors and bank syndicates. The latter requires that the new issue to price after expiry of the tender offer, and is thus less common.

A timeless trend

The surge in bond buyback transactions, seen since the start of the year, is an underlying trend that is here to stay. All told, the more or less favorable interest rate environment weighs less on issuers’ decisions than their own particular situations.

There is always a good reason to launch a debt management transaction. One of the main difficulties is identifying holders of the debt. Banks are therefore charged with assisting the issuer in their approach to attempt to identify holders and their intentions during the offer period.

Pros and Cons